Intuit is a company that cares deeply about our customers.

Our mission is to power prosperity around the world by helping approximately 100M consumers, small businesses and self-employed individuals overcome their most important financial challenges with TurboTax, QuickBooks, and Credit Karma. Among our 2025 aspirations and bold goals is to help double the household savings rate and improve the small business success rate.

Accessibility is a natural fit for Intuit’s mission of financial empowerment. Our products are more than web, desktop, and mobile applications—they’re tools that enable people to lead independent financial lives. To that end, we’re dedicated to making sure that our products reach everyone, regardless of their physical, sensory, or cognitive ability.

As Intuit’s Global Accessibility Leader, I’m proud of how our company fosters a culture where everyone works to accommodate the needs of all customers by not only delivering accessible products, but engaging with customers, communities and like-minded organizations committed to driving innovation for accessibility.

Here are five grassroots approaches we’ve taken that are making a difference in day-to-day lives—and livelihoods.

Creating an Accessibility Champion Program

Historically, accessibility teams are small, centralized teams including subject matter experts. They provide a leadership role, testing, design reviews, and education. But their influence is limited by their size and resources. Accessibility Champion programs break this silo and extend leadership across the company.

Historically, accessibility teams are small, centralized teams including subject matter experts. They provide a leadership role, testing, design reviews, and education. But their influence is limited by their size and resources. Accessibility Champion programs break this silo and extend leadership across the company.

Each company will take a unique approach to building a community of accessibility champions. Some will have subject matter experts embedded within business units and products. Some will focus on allyship, giving everyone an opportunity to learn about accessibility led by a centralized leadership team. At Intuit, we created an accessibility champion program that sits in the middle. Everyone can become a Level 1 Champion with basic accessibility and disability etiquette knowledge. There’s also a roadmap for people to become Level 2 champions and lead their product teams and locations. Our subject matter experts are at Level 3 and they influence Intuit and our communities.

In two years, Intuit has almost 900 Accessibility Champions and their impact has been inspiring. Accessibility is part of the daily conversation across the company. Our champions are taking on projects the centralized team could never have imagined. They have the confidence to drive changes and many product teams have moved to an accessibility-first development methodology. Our connection with communities has grown through volunteering, conference talks, customer interviews, open source contributions, and publications.

Developing Employment Opportunities

The unemployment and underemployment rate for people with disabilities is tragically high. Unfortunately, people applying for a job not only have to prove they are qualified, they also have to prove they are capable. Many job seekers are over-qualified, but education and work experience don’t match the narrow expectations of employers.

Intuit started our process by looking internally. We’ve re-evaluated our job descriptions to remove unconscious bias. An example change was replacing “Must have excellent written and oral communication” with “Must have excellent written and/or oral communication.” While not everyone is able to both write and speak, many are still excellent communicators. Our talent teams include training for disability etiquette and inclusive hiring.

Intuit’s recruiting efforts now include university disabled student service departments. And, we’re excited to start a partnership with the United Spinal Association’s Tech Access initiative to support the pursuit of job opportunities for people with spinal cord injuries and disorders.

Like many technology companies, Intuit understands the strengths and needs of neurodiverse individuals. To that end, we’ve partnered with Integrate, an organization for autism employment opportunities, to connect students with Intuit leaders for mock job interviews, coaching, and hiring. And, a few years ago, before it became more of a common industry practice, we extended benefits coverage for employees with neurodiverse family members to include applied behavioral analysis (ABA), physical, speech and occupational therapies.

Fostering an Entrepreneurial Spirit with Small Businesses

Entrepreneurship and self-employment are oftentimes the only employment opportunity for people with a disability. Our goal is to develop strong small businesses that increase hiring of others with disabilities.

Photo credit: Mozzeria

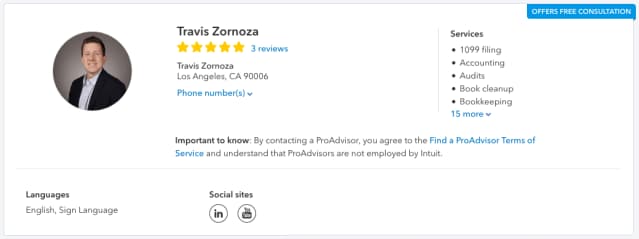

One great example is Mozzeria, a San Francisco-based pizzeria founded in 2011 that is deaf-owned and operated. Their goal was to make delicious food, create a deaf-friendly community space, and increase employment opportunities within the Deaf community. The QuickBooks team met Mozzeria for a customer interview at the restaurant. Their feedback about the challenges of finding an accountant that communicates with ASL (American Sign Language) led us to add language support as an attribute to Intuit ProAdvisor accountant profiles.

In 2020, Mozzeria expanded from San Francisco to Washington, DC — during a global pandemic, no less! Under a guiding principle that “Neapolitan pizza and sign language are our love languages,” the pizzeria is bringing a welcoming, memorable, and visual environment for more customers to experience Deaf culture, while creating career placement opportunities for Deaf people.

Deaf entrepreneurs need advice on creating business models, finding an accountant, marketing, and using QuickBooks software in their primary language, American Sign Language. Yantern’s online webinars, one-on-one consulting, and virtual conferences help them prepare and launch their businesses. Intuit has been a founding sponsor of their events and provides discounted software to their clients.

Another excellent example is a small ice cream shop near our Bangalore, India office. Intuit supports the National Association for the Blind Karnataka, an organization that provides entrepreneurship opportunities for people who are blind or visually impaired in rural India. Pramod Ice Cream started with a single ice cream machine and now has a vibrant store with 13 employees of varying abilities.

Photo credit: Ted Drake

Intuit continues to support key organizations working with entrepreneurs.

For example, Aira provides remote sighted assistance via mobile phones and computers. Their highly trained agents describe the environment, documents, and interactions. Intuit sponsors Aira usage for all blind and low vision small business owners. Many small business owners use Aria to read contracts, review their workplace, complete inventory, do research, read brochures, explore trade shows, and complete a task on software that is not accessible.

It’s a little known fact that most vending machines, concession stands, and cafes on state and federal properties are owned and operated by entrepreneurs who are blind or have low vision. The Randolph Sheppard Vendors Act was created in 1936 to support these small businesses. Intuit sponsors the annual Sagebrush conference for entrepreneurship development.

Driving Education and Awareness from the Inside Out

Unfortunately, accessibility is not included in most computer science curriculum, which requires technology companies to fill the gap with bootcamps, workshops, and onboarding instructions. Intuit is a founding member of Teach Access, a collaboration between technology companies and universities. Teach Access provides university professors with high quality instruction material, grants, and students get direct access to accessibility leaders at Verizon, Google, Facebook, Intuit, and many more companies.

Intuit was also a founding member of the International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP) and encourages our Level 3 Champions to complete their IAAP Certifications. The IAAP provides professional development for the next generation of accessibility leaders.

Intuit’s Accessibility Champions have developed creative opportunities for learning more about design and engineering. During the 2020 COVID shutdown, we launched a series of lunch and learn lectures, workshops, and online courses. More than 550 people attended accessibility sessions. We’ve also created more than 15 courses that focus on general and specific topics, such as ableism, inclusive design, and dyslexia. To further support individualized learning, we’ve curated a collection of videos for people to explore design, engineering, and accommodations in multiple languages.

Engaging with Communities we Serve

Intuit embraces community involvement. Through our “We Care and Give Back” program, eligible employees are given time to volunteer with organizations of their choice, donations are matched, and we embrace opportunities to work directly with our customers. Our Accessibility Champions program includes volunteering as an individual and/or group within the roadmap for leadership growth. Accessibility Champions have volunteered with more than 30 organizations around the world.